The poets of the present day who would raise the epic song cry out, like Archimedes of old, "give us a place to stand on and we will move the world." This is, as we conceive, the true difficulty.

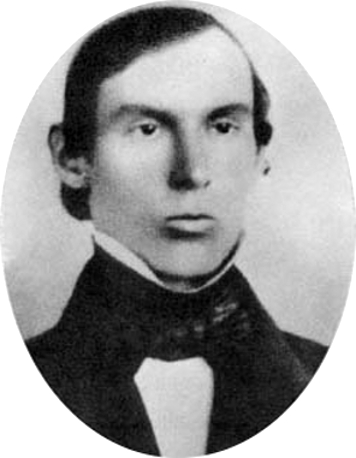

"Jones Very" was an American poet, essayist, clergyman, and mystic associated with the American Transcendentalism movement. He was known as a scholar of William Shakespeare and many of his poems were Shakespearean sonnets. He was well-known and respected amongst the Transcendentalists, though he had a mental breakdown early in his career.

Born in Salem, Massachusetts to two unwed cousin/first cousins, Jones Very became associated with Harvard University, first as an undergraduate, then as a student in the Harvard Divinity School and as a tutor of Greek language/Greek. He heavily studied epic poetry and was invited to lecture on the topic in his home town, which drew the attention of Ralph Waldo Emerson. Soon after, Very asserted that he was the Second Coming of Christ, which resulted in his dismissal from Harvard and his eventual institutionalization in an psychiatric hospital/insane asylum. When he was released, Emerson helped him issue a collection called Essays and Poems in 1839. Very lived the majority of his life as a recluse from then on, issuing poetry only sparingly. He died in 1880.

If you enjoy these quotes, be sure to check out other famous poets! More Jones Very on Wikipedia.Do we wonder then, that, as this momentary petrifaction of the heart goes on, we are every day more and more strangers in this world of love, holding no communion with the Universal Parent, and hoarding up instead of distributing His general gifts?

Often and often must he have thought, that, to be or not to be forever, was a question, which must be settled; as it is the foundation, and the only foundation upon which we feel that there can rest one thought, one feeling, or one purpose worthy of a human soul.

From the wrestling of his own soul with the great enemy, comes that depth and mystery which startles us in Hamlet.

As long as man labors for a physical existence, though an act of necessity almost, he is yet natural; it is life, though that of this world, for which he instinctively works.

IT is pleasing to frequent the places from which the feet of those whom this world calls great have passed away, to see the same groves and streams that they saw, to hear the same sabbath bells, to linger beneath the roof under which they lived, and be shaded by the same tree which shaded them.

The stream of life, - which, in other men, obstructed and at last stationary as the objects that surround it, seems scarcely to deserve the name,- in them rolls ever onward its rich and life-giving waters as if unconscious of the beautiful banks it has overflowed with fertility.

The simplest conception of the origin and plan of the Iliad must, we think, prove the most correct. It originated, doubtless, in that desire, which every great poet must especially feel, of revealing to his age forms of nobler beauty and heroism than dwell in the minds of those around him.

These are matters of external history. They are indeed prominent objects, often changing and giving a new direction to the current; but they tell us not why it flows onward and will ever flow.

Copyright © 2024 Electric Goat Media. All Rights Reserved.